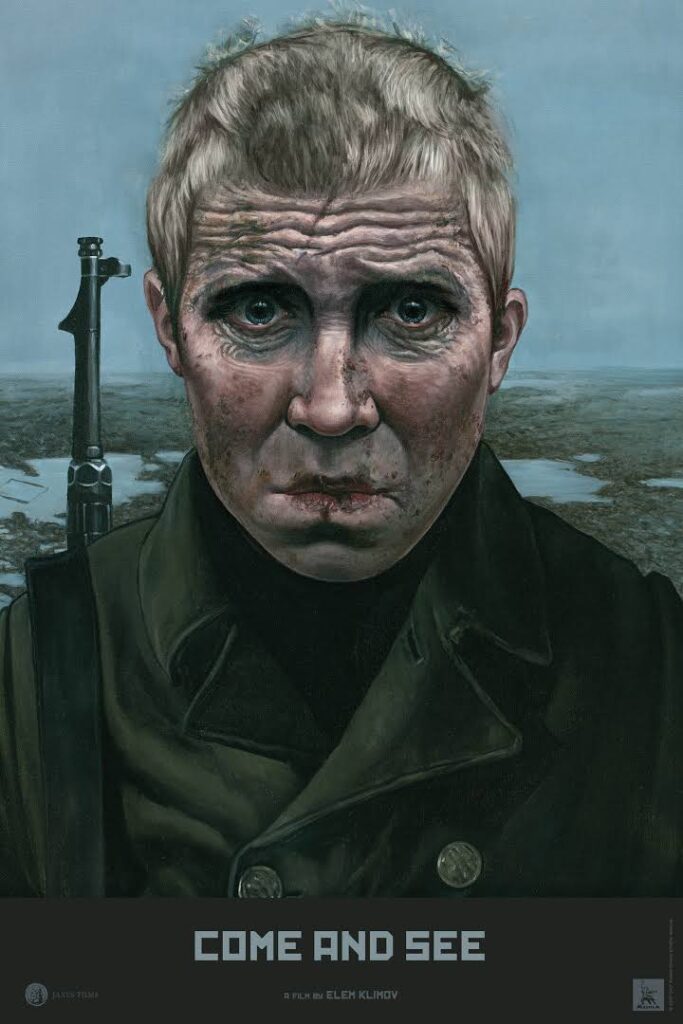

The Second World War brought massive destruction and loss to Europe from displaced people, sicknesses, injuries, and death. Filmmakers impacted by these tragedies have taken to cinematography and film as a form of expression to show the horrible image of the war. One of the most outstanding films portraying the Second World War is Idi i smotri/ Come and See (Elem Klimov, 1985). It is a Soviet production that portrays the Nazi German occupation of Byelorussia and the role of the Soviet’s resistance in the war. The main character is a young boy who is, directly and indirectly, involved in the war. Accordingly, he loses his family. The scene where he realizes the death of his family is the chosen scene for this essay which presents several symbolic elements. Additionally, several cartographic techniques in the use of the camera and sound engineering support the scene Amazingly.

During the Second World War from 1941 – 1944, the Nazi Germans destroyed 600 Byelorussian villages and their inhabitants (Rowan, 2012: 96). Come and See is an outstanding film that portrays the intensity and the horror of the war. The film is a 1985 psychological Soviet war film in the style of a documentary-drama film. It is directed by Elem Klimov and written by Ales Adamovi, and starring Aleksei Kravchenko in the main role of Florya, Olga Mironova as Glasha, and Liubomiras Laucevicius as Kosach (IMDb, 2017). The film is based on the memories of Adamovich showing the German army’s reprisals during the occupation of the Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia (Rowan, 2012: 96). The director Klimov struggled against Goskino, the USSR State Committee for Cinematography in the Soviet Union, for the rights of freedom of artistic expression. It should be noted that Goskino blocked come and See for eight years (Lawton, 1992: 54). Nevertheless, the film broke the most taboo of all subjects of the war, which was showing Soviet citizens passively and actively while collaborating with Nazis to commit murders in Belorussia. The reality of the war is portrayed along with the devastating loss of millions of citizens in its course (Gershenson, 2013: 264).

Come and See is an emotionally harrowing yet most realistic tale of the war in Byelorussia. The narrative has loosely connected parts and shows critical situations with a loose structure. It is told from the point of view of a young teenager (Chapman, 2008: 104). The film starts by showing Florya and another boy digging in the sand, looking for weapons that allow them to join the Soviet forces against the German invasion in 1943, and there is an elder discouraging them from digging. Against his family’s wishes, Florya finds a rifle and afterwards joins the resistance. Unfortunately, He has been ordered to give his footwear to another and to stay in the camp. In the forest, he meets Glasha, who accompanies him back to his village, where they find out that Florya’s family and other villagers were massacred. Eventually, they met a partisan fighter, Roubej, who took them to a nearby partisan camp where Florya’s villagers were also. That camp provided shelter for the villagers, which included a horribly burned elder lying on his back. He was the same man who was trying to get them to stop digging at the beginning of the film. At this moment, Florya is traumatized by the death of his family, holding himself responsible (Come and see, 1985).

It is worth mentioning that the war between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany did not really affect Russia as much as the other countries, and most of the destructed lands were non-Russians. Byelorussia was particularly destroyed as it is located in the middle between the two powers, which made its lands be occupied since the beginning of the war in 1939 (Bohdan, 2012). Come and See was released to mark the 40th anniversary of the Soviet/ Red Army’s victory over Nazi Germany (Dunne, 2016). This chosen scene shows some partisans helping the villagers and accommodating them. However, the fate of these activists resulted in a brutal collective punishment on behalf of the German administration (Bohdan, 2012).

The situation of the burned elder can be described as a third-degree burn all over the dying man’s body. He says, “Dead to the last one. To the very last one … I burned. I begged them to kill me. They just laughed” (Come and see, 1985). He was slaughtered with other civilians in a cabin by the Nazi patrol as part of a brutal joke. The film is packed with horrible images of what the Nazi Germans did in Byelorussia, including striking, murdering, torturing, and raping.

The cinematography of Come and see has interested many cinema critics and students. Klimov used non-professional actors and employed widescreen and Steadicam to create a sense of immediacy with his cameraman Alexei Rodionov. The film is full of extreme close-ups of faces and shows unpleasant details of burnt flesh and bloodied bodies. Moreover, there are some jarring edits. Specifically, this scene includes some aspects regarding the form and content (film). When Florya realizes that his family was killed, the shocking moment is marked by a disorienting zoom-in/ dolly-out shot (Chapman, 2008: 106). It is also called the vertigo effect, which can be seen when the camera is physically pulled away from the subject while the lens zooms in. The effect is famous for creating a visually jarring scene to mirror the psychological turmoil of the characters (Averbeck, 2015: 401). Additionally, with the use of sound, Klimov underscores Flyora’s psychological breakdown that the hope of erasing his trauma is impossible. The audience is hearing exactly what Flyora hears. The elder’s words were so important that the sound of the crowd mutes, and when Florya tries to bury his head in a patch of muddy earth, the sound of the crowd remains as loaded as ever. Klimov uses images and sounds to let the audience take part and feel Flyora’s feelings (Dunne, 2016).

In conclusion, during the Second World War, most of the conflicts between the Soviet forces and the Nazi Germans were concentrated in Byelorussia. Come and See is a film presenting horror images of what happened during the war in a documentary-drama style. The narrative is episodic, not structurally connected, and the story is told from the point of view of a young Flyora. He wants to join the resistance, but unfortunately, he is treated as a useless soldier. When he goes back to his village, he finds that some of the villagers fled, and most of them were murdered, including his family. The realization of all the murdering finally hit him when he saw the brutally burned elder in a situation that reflected the image of what the Nazi Germans did in Byelorussia. Flyora is traumatized by the death of his family and held himself responsible. Additionally, the scene presents the role of the resistance during the war. Klimov shot this scene considering the effect on the audience. He supported the performance of the characters with several technical aspects in shooting and sound. As a result, the audience should empathize with the tragic scene feeling and strong emotions toward the moment and the characters presented.

___

Bibliography

Averbeck, J. (2015). A Hitch at the Fairmont. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Bohdan, S. (2012). Why Belarus is Missing in World War II History. BelarusDigest. Available at: https://belarusdigest.com/story/why-belarus-is-missing-in-world-war-ii-history/ [Accessed 13 Dec. 2017].

Chapman, J. (2008). War and Film. London: Reaktion Books.

Come and see. (1985). [DVD] Directed by E. Klimov. Soviet Union: Belarusfilm.

Dunne, N. (2016). Atrocity exhibition: is Come and See Russia’s greatest ever war film?. The Calvert Journal. Available at: https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/6415/come-and-see-elem-klimov-war-film-bastards-star-brest-fortress [Accessed 13 Dec. 2017].

Gershenson, O. (2013). The Phantom Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and Jewish Catastrophe. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

IMDb (2017). Come and See (1985). IMDb. Available at: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0091251/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2017].

Lawton, A. (1992). Kinoglasnost: Soviet Cinema in Our Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rowan, T. (2012). WOrld War II Goes to the Movies & Television Guide. Morrisville, NC: Lulu.