By Yousif Al Hamadi

The exact origin of animation might be challenging to pinpoint, however after tracing its roots, findings of explorations of moving images in prehistoric sites have appeared dating thousands of years. Developments during the Industrial Revolution era also brought many inventions and experiments that influenced the improvement of animation. Some pioneer animators identified animation in form and content from live-action films, which also developed in parallel. They were primarily cartoonists, such as James Stuart Blackton, Emile Cohl, and Winsor McCay, who worked at daily newspapers.

Many technological, cultural, industrial, and aesthetic factors were involved in improving and developing animation throughout history to turn the art form into an industry. Animation is a broad field, and it is not easy to define its root. In 1940, Lascaux caves were discovered in southwestern France with paintings of animals covering the interior walls and ceilings dating 15,000 BCE. The animals were painted in sequence with slight changes in position, suggesting an early interest in animated movements (Furniss, 2017: 12-13). The Industrial Revolution and the chase after modernization supported the development of art and entertainment. One of the most significant inventions during that time was the magic lantern system invented in the 17th century. It was an image projector showing hand-painted glass slides. The popularity of the magic lantern shows it sustained throughout the 19th century. Meanwhile, a range of other optical toys, such as the Thaumatrope, Zeotrope, and praxinoscope, were invented to increase scientific and optical principles and create entertaining visual effects (Kuhn and Westwell, 2012: 252-253). Additionally, the invention of photography made a shift in modern culture. It was created for scientific and technological purposes, but it progressed in its usage towards methods and reception of animation (Furniss, 2017: 18-20). For example, in 1877, the English photographer Eadweard Muybridge presented studies of animal locomotion by using a series of cameras placed in a row. He presented a single photographic negative of twenty-four images showing a movement of a man riding a horse (Popova, 2011)

and Saint John the Baptist

Possibly, the most influential aspect was when illustrations started to be used in storybooks. Some books do not have pictures, but most children books do to explain words. Several kinds of illustrations were described as a cartoon. Originally, the cartoon was a type of charcoal sketches used as a guide for paintings, such as Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist. Currently, the term cartoon mostly describes a type of graphic art of bold drawings with clear lines. Daily newspapers used to publish different kinds of cartoons, such as caricatures. They are funny drawings that exaggerate known figures features, with or without speech, and present one idea. Other types of cartoons, such as comic books and cartoon strips, are expressed in pictures, and each picture or frame easily follows the one before it (Gogerty, 2003: 34-38). Accordingly, animation attempted to recreate a graphical physical movement. Animated drawing and paintings and live-action films have similarities regarding moving picture on the screen. However, the animation is more flexible and creative than live-action because there is a vast space to exaggerate physical possibilities by speeding movement up or slowing it down in a comical or expressive style. Animation production for Children may have monopolized a large part of the field. Still, many works address issues and topics for adults produced professionally or for educational purposes (Halas, 1987: 9).

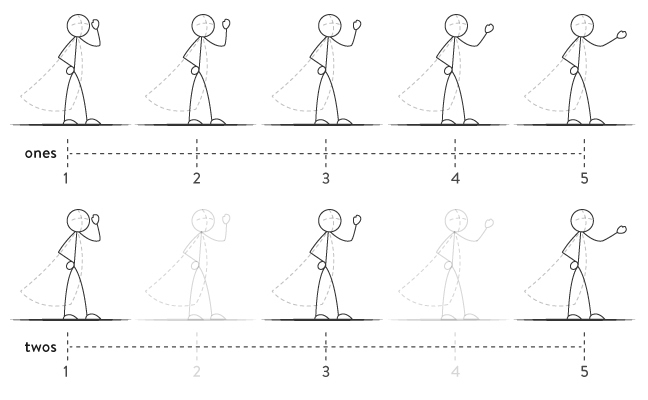

The noun Animation was identified originally from the Latin animatus, which essentially means ‘give breath to’, while anima means ‘life or breath’, and ane means ‘to breathe’ (Etymonline.com, 2018). The term has been used to describe a range of practices in which the movement of forms creates an illusion of motion sequentially displaced as a motion picture. (Furniss, 2017: 12). To understand the basis of the motion picture, the physiological aspect needs to be considered, which is also known as the persistence of vision. It occurs as a phenomenon because the human eye’s retina can retain an image of an object for about one-third of a second after the object is removed from view. Therefore, if a series of still images (frames) were presented in a rapid sequence, it will give the appearance of movement in a continuous action as an optical illusion (Halas, 1987: 11). To avoid jerks and jumps in motion, the frame rate must be sixteen frames per second or more. Animation creates the illusion of movement by photographing drawings, puppets, or nonliving objects, and the effect is simulated through making slight progressive changes from a frame to the next one (Kuhn and Westwell, 2012: 11).

Animation includes a variety of techniques. Roughly the oldest is Stop-motion animation. It is a technique manipulating physical objects such as clay or plasticine like Wallace and Gromit by Nick Park of Aardman Animations, or paper cutouts as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (Lotte Reiniger, 1926). The animator moves these objects frame-by-frame to produce the illusion of movement. Another technique is called cel animation. It is a traditional technique that photographs hand-drawn images and uses transparent clear celluloid sheets or cels, allowing multiple layers to be combined over the same background. Moreover, rotoscoping was used in early cartoons to speed up animation production by tracing animated photography (Cateridge, 2015: 124). Recently, computer animation is being used extensively in creating animation films. It composites graphic and photographic elements as much as the animation scene needs using software tools. Nowadays, movements can be recorded by real actors to be applied to characters digitally using motion capture. Additionally, realistic-looking images and environments are easily created using sophisticated texture and lighting rendering techniques leading to massive cooperation in live-action such as Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993) (Chandler and Munday, 2011: 16). During the digital age, video games have been combined with films to create forms of animation such as machinima. It is used within video games to develop sequential animation involving multiple shots, characters, and dialogue (Cateridge, 2015: 125).

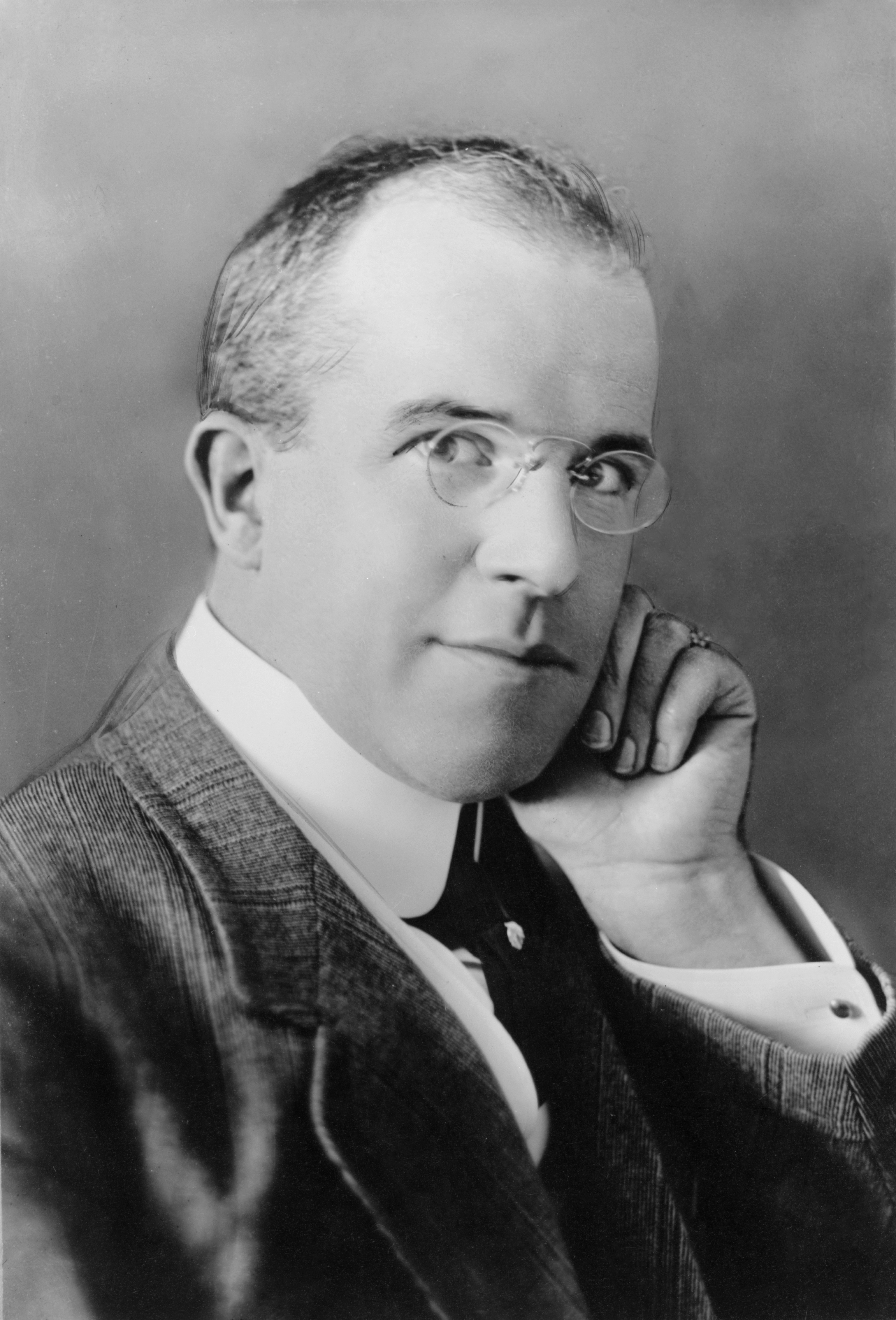

James Stuart Blackton (1875 -1941) was a pioneering animator who linked animated cartoon and live-action film through many experiments and innovations. Blackton was originally from Britain and moved to America when he was a child. He became a journalist and was a well-known illustrator at New York World (Halas, 1987: 18), a newspaper established in 1860 until 1931 published popular comic strips, such as The Yellow Kid (Simkin, 2014). In this stage, the technology of animation was a spectacle, and live-action cinema was becoming commonplace. The American inventor and businessman Thomas Edison collaborated with Blackton at Edison’s laboratory to demonstrate animated filmmaking. The footage later was released in 1900 as a film, The Enchanted Drawing. It shows Blackton drawing a face on a large pad, and series of tricks occur. For example, drawn objects – a hat, a bottle, a glass, and a cigar – magically become real objects on the screen by stopping the camera and substituting them into the frame while the camera is off. Meanwhile, the drawn face changes his expression as another example of substitution through stop-action photography. (Wood, 2012: 17).

Blackton was accredited with making the first film-based animation with Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) (Crow, 2014). He collaborated with an expert cameraman, Albert Smith, who developed the vitagraph invention and opened a studio with the same name. The Vitagraph was a constructed Kinetoscope for trick photography that allowed them to control the amount of light to film the needed background, be used later beneath the stop motion part, and adjust the sequence frame by frame (Halas, 1987: 19). The film includes a range of tricks. For example, it begins with the title that appears as a stop motion cutout on the frame. The action starts with Blackton’s hand drawing a man’s head on a board to show the ability of the animator to bring the images to life as the original meaning of animation. The hand of the artist then became a motif during the silent cinema period. Also, stop motion was employed at the end of the film when a drawn clown is shown, while his legs and arms are cutout to move freely along with a cutout dog and hoop (Furniss, 2017: 32). It should also e noted that Blackton spent a long time making the film. He needed to draw more than 3000 drawings to achieve his desired results. He also made other animated films, such as The Haunted Hotel (1907), imported by France and shown at the Châtelet in Paris (Halas, 1987: 19).

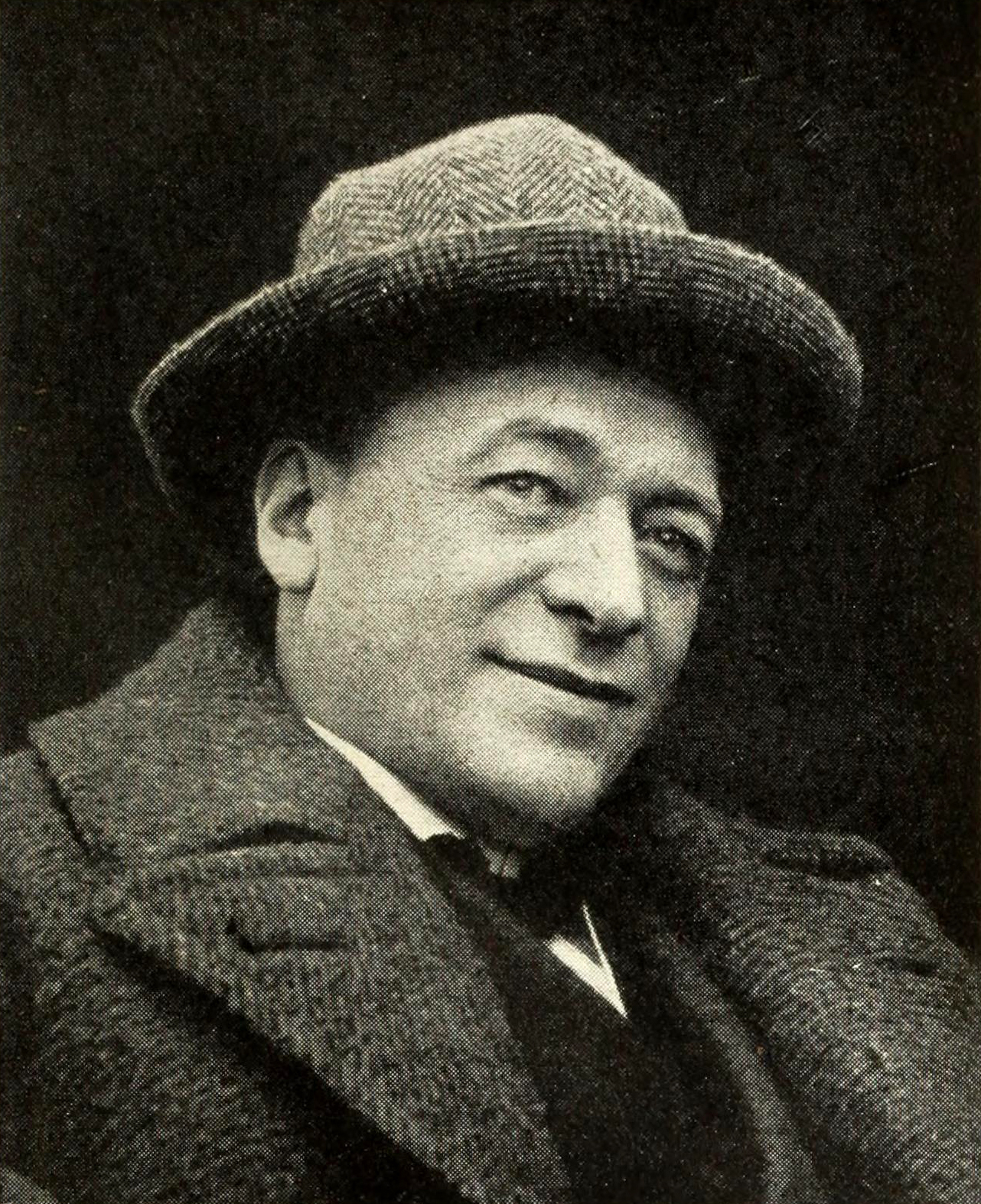

Émile Cohl (1857- 1938) is another pioneering animator who used to be a print cartoonist. He was quite a diverse artist, painting, illustrating, writing pottery, and editing literature (Furniss, 2017: 40). In 1879 he published some caricatures of the unpopular president Patrice MacMahon who did not hold out for more than three months, whilst Cohl had a job as an editor at the political publication L’Hydropathe. He also joined an artistic movement, the Incoherent, during the 1880s. It was an avant-garde movement that reflected dream imageries, with a fascination with unrefined and children’s drawing styles (O’Brian, 2013). Additionally, he was aware of the motion picture film camera, the cinematograph, which was invented in 1896 by the Lumière brothers, and was intrigued by the projections of the illusionist and film director Georges Méliès which were shown in local halls and theatres. How Cohl became involved in cinema was not a coincidence. In 1936, he had an interview with the cultural newspaper, Comoedia. He said that he was surprised when he saw a poster of a film in the street by Gaumont studio inspired by one of his drawings and that the manager of Gaumont offered him employment on the spot as a scenarist. Cohl immediately accepted (Crafton, 2014: 91- 93).

In 1908, Cohl created his first animation, Fantasmagorie, for Gaumont in the hand-drawn traditional style. The name is referred to as the fantasmograph, a type of magic lantern (Press, 2016), and the term means an imaginary sequence of changing scenes like a dream (thefreedictionary.com, 2018). The film structure was created as an experiment to be rather spectated more than narrative. Cohl achieved an extraordinary fluidity of movement by creating 700 drawings and projecting them as 16 frames per second. Fantasmagorie begins and ends with the artist’s hand, brings a stick figure of a clown to life, drifts in and out, and objects around it morph into other forms. It was inspired by Blackton’s style, using white drawings of chalk lines on a blackboard, which was achieved by reversing the print of black lines on white paper after filming (Furniss, 2017: 40). Among Cohl’s technical accomplishments was the use of matte photography for the first time to composite live-action with animation in The Man in the Moon (1909). He also relied on cutouts in many of his films, such as The Twelve Labors of Hercules (1910) and The Neo-Impressionist Painter (1910). Moreover, Cohl travelled to the United States between 1912 and 1914, where he worked with George McManus’s famous American comic strip The Newlyweds. The last significant film by Cohl was The Puppet House (1921) (Crafton, 1993: 74-84).

Winsor McCay (1869-1934) was also an influential, pioneering animator. He started his career by illustrating circus posters in Chicago at age twenty one. In the following years, he became a strip cartoonist at several newspapers in Chicago, Ohio, and New York. His work was known for the vast amount of detail, fine lines, speed drawing, and the strong style of art conveying topics about real life. McCay dominated the theme of fantasy, and most of his work was experimenting with visual composition through a set of graphical standards. The most famous strips were Little Sammy sneeze (1904-6), Dream of the Rabbit Fiend (1904-11), and the masterpiece Little Nemo in Slumberland which began in 1905 (Blazquez, 2013). He was inspired by the works of Blackton and Cohl and started to think about animating his cartoon. He worked with Blackton and produced Little Nemo (1911). The animation in the film is a small part of a live-action film that Blackton directed in Vitagraph. McCay featured three characters of the strip Little Nemo in Slumberland: Nemo, Impie, and Flip are standing in a row, tumbling, rotating, rolling, and stretching. Additionally, the animation has depth operating in naturalistic movements and realistic timing with four thousand drawings. McCay’s animation received positive reviews showing him as the one who upgraded the form narratively, artistically, and technically (Eagan, 2011).

The ability to give a personality to characters is one of the distinctive features known about McCay’s animation. In 1912 he created How a Mosquito Operates, while the story was taken from Dream of the Rabbit Fiend strip. The personality of the mosquito is well treated. It wears a hat and carries a suitcase, is playful, a showoff attacks a sleeping man and is named Steve (Grob, 2010). In the following film, Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), McCay interacts with Gertie in front of an audience after a live-action intro. Gertie is a shy dinosaur, but seems to be alive, playful, thinks, breathes, and is unpredictable. According to John Canemaker, McCay invented the ‘in betweening’ by breaking the motion down to certain poses drawn first. Then later, the missing materials were filled between them. For this film, 10,000 drawings were made consisting of the background and Gertie, which was redrawn in each frame. During this time, there were no other advanced technological methods of keeping objects fixed frame by frame (Eagan, 2009). The use of celluloid drawing sheets entered the world of animation in the mid-1910s. McCay utilized cel animation in his political cartoon, The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918), which documented the sinking of the British passenger ship by German boats in 1915. The last animation film created by Winsor McCay was The Flying House (1921). (Furniss, 2017: 42-43).

In conclusion, many technological, cultural, industrial, and aesthetic factors were involved in animation development throughout history. The most significant inventions were the magic lantern, a range of optical toys, and photography. Additionally, cartoon and illustrations in newspapers and comic books were also an important aspect added to the practices, methods, and reception of animation, whether targeting children or adults. The term has been used to describe a range of techniques in which the movement of forms create an illusion of motion. Live-action films and animation were likewise regarding the development of the movement of a motion picture on the screen and the use of the phenomenon of persistence of vision in the human eye. Still, the animation was more flexible and creative with physical possibilities in treating ideas and concepts. However, there are several techniques to create animation films, such as stop motion, cel animation, rotoscoping, and recently the whole industry was computerized and digitalized. The most influential pioneering animators started as strip cartoonists and were experimenting with animation, such as James Stuart Blackton, who linked animated cartoon and live-action film and was accredited with making the first animation based film, Humorous Phases of Funny Faces; Emile Cohl, who achieved an extraordinary fluidity of movement with his first hand-drawn traditional style of animation Fantasmagorie; and Winsor McCay who created an animation with depth that operated naturalistically, upgraded animation narratively, and gave a personality to his character such as the dinosaur in Gertie the Dinosaur.

___

Bibliography

Blazquez, D. (2013). Winsor McCay: About Fame and the Enjoyment of Art. The Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies. Available at: https://www.rockwell-center.org/student-research/winsor-mccay-about-fame-and-the-enjoyment-of-art/ [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

Cateridge, J. (2015). Film Studies for Dummies. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Chandler, D. and Munday, R. (2011). A Dictionary of Media and Communication. Oxford: Oxford

Crafton, D. (2014). Emile Cohl, Caricature, and Film. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. University Press.

Crafton, D. (2015). Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Crow, J. (2014). Watch Humorous Phases of Funny Faces, the First Animated Movie (1906). Open Culture. Available at: http://www.openculture.com/2014/09/watch-humorous-phases-of-funny-faces-the-first-animated-movie-1906.html [Accessed 14 Mar. 2018].

Eagan, D. (2011). Little Nemo. Loc.gov. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/programs/static/national-film-preservation-board/documents/little_nemo.pdf [Accessed 18 Mar. 2018].

Eagan, D. (2009). Gertie the Dinosaur. Loc.gov. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/programs/static/national-film-preservation-board/documents/gertie.pdf [Accessed 19 Mar. 2018].

Etymonline.com. (2018). animate | origin and meaning of animate by Online Etymology Dictionary. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/animate [Accessed 24 Feb. 2018].

Furniss, M. (2017). Animation: The Global History. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Gogerty, C. (2003). Stories in Art. Buckinghamshire: Cherrytree Books.

Grob, G. (2010). How A Mosquito Operates. Dr. Grob’s Animation Review. Available at: https://drgrobsanimationreview.com/2010/06/20/how-a-mosquito-operates/ [Accessed 19 Mar. 2018].

Halas, J. (1987). Masters of Animation. London: BBC Books.

Kuhn, A. and Westwell, G. (2012). A Dictionary of Film Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Brian, B. (2013). The Incoherent Animation of Émile Cohl. Pretty Clever Films. Available at: http://prettycleverfilms.com/saturday-morning-cartoons/the-incoherent-emile-cohl/#.WqqBb0x2tPY [Accessed 15 Mar. 2018].

Popova, M. (2011). Before Walt Disney: 5 Animations by Early Cinema Pioneers. brainpickings.org. Available at: https://www.brainpickings.org/2011/07/05/animation-pioneers/ [Accessed 17 Mar. 2018].

Press, G. (2016). Animation Firsts and the Birth of HP: This Week in Tech History. Forbes.com. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/gilpress/2016/08/14/animation-firsts-and-the-birth-of-hp-this-week-in-tech-history/#60d90ab3eed3 [Accessed 16 Mar. 2018].

Simkin, J. (2014). The New York World. Spartacus Educational. Available at: http://spartacus-educational.com/USAnyworld.htm [Accessed 13 Mar. 2018].

thefreedictionary.com (2018). Phantasmagories. thefreedictionary.com. Available at: https://www.thefreedictionary.com/phantasmagories [Accessed 16 Mar. 2018].

Thomas, M. and Penz, F. (2003). Architectures of Illusion: From Motion Pictures to Navigable Interactive Environments. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Wood, A. (2012). Digital Encounters. London: Routledge.