By Yousif Al Hamadi

Introduction

Islamic architecture is distinguished by the style of mosques upholding their own distinctive architectural characteristics. Oleg Grabar said the mosque carries symbolic signs. Some are religious and exist in every mosque, such as the mihrab, or administrative, such as the minbar, or associated with the ruler, such as the maqsura, or official, such as the distribution of aisles in the prayer hall, and some of them change their cause over time, such as the minaret. These elements are variable according to the geographical location of the mosque. They have their own circumstances, and they are constantly evolving, but they do not lose their peculiarity.[1]

The ever so famous Zaytuna Mosque in Tunis portrays an Arab style, its simplicity has been valued throughout history. Yet, it has been expanded several times without losing its basic components. For more than ten centuries, this monument has been an example of Islamic architecture and an example of North African architecture. When Tunis was founded, it was nothing but a small city, and the Zaytuna Mosque was just a place to hold prayers. Still, most of the rulers and dynasties who ruled this city endeavored to register their names in developing its architecture until the mosque became one of the most important achievements throughout Islamic history.

Throughout North Africa, starting with Libya and ending in Morocco, and passing through Tunisia and Algeria, three mosques have emerged that have had, and still are, in Islamic history a significant share of interest between Muslim and non-Muslim researchers and historians. These mosques were established in the first centuries after the immigration of the Prophet Mohammed to Medina. First, the Kairouan mosque was built by Uqba ibn Nafi in 671 when he entered Ifriqiya. Second, the Zaytuna Mosque was built by Hassan ibn Numan, who founded the city of Tunis in 702. Third, the Karaouine mosque was built in 859 in Fez by Fatima al-Fihri, who was originally from Kairouan and was taking Fez as her homeland.

This essay presents information about the condition, which led the Zaytuna mosque to be built, who built it, the expansion and restoration, its location, a detailed analysis of its main structure, sanctuary, domes, mihrab, and minaret. It also offers a comparison between the mosque of Kairouan and the Zaytuna mosque.

History

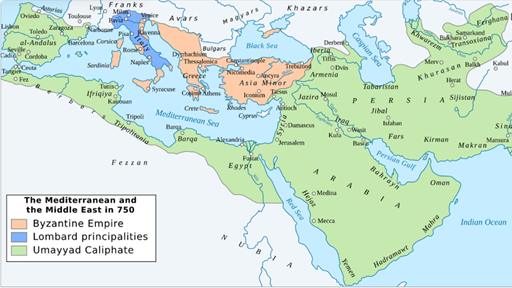

The conflict between the Muslims and the Byzantines began in North Africa (Ifriqiya) during the reign of Caliph Uthman bin Affan (r. 644–656) and the first campaign to conquer it was in 647. At that time, the Byzantines had a base in the city of Carthage. However, Ifriqiya and Maghrib were not easy bites because of the resistance of the Berber tribes, which were allied with the Byzantines. Therefore, during the Umayyads caliphate (661–750), the Muslims founded the city of Kairouan in 670, away from the Byzantines fleet by the general Uqba ibn Nafi.[2] It was designed to spread Islam as a garrison city, military supply base, and fulfilling other Muslim cities with “pasture, firewood, building material, natural defense and so on”[3]. In Kairouan, Uqba and some of the prophet’s companions built the fourth great mosque of Islam, the great mosque of Kairouan.[4]

The conflict between the Muslims and the Byzantines and their allied Berber tribes continued until the time of the Umayyad Caliph Abdul Malik bin Marwan (r. 684-705), who prepared an army and placed it under Hassan ibn Numan. Hassan was able to defeat the Byzantines and their allies and destroyed Carthage in 702. He then established Tunis. A large lagoon separating it from the sea protected it from the Byzantine naval attack.[5] After that, he focused on organizing Ifriqiya by creating governmental departments (diwans), systematizing the tax (Kharaj), appointing governors in different regions, building a naval base, shipyard, arsenal (dar al-sina’ah), and building the Zaytuna mosque in Tunis, the great mosque of Tunis.[6] After thirty years, Ubayd Allah ibn al-Habhab made the city more robust. He built new docks, enlarged the shipyard, and encouraged immigration to the city to increase its population. He also enlarged the Zaytuna mosque.[7]

It seems that there is a doubt about who built the Zaytuna mosque. There are who claim that the mosque was built based on the order of caliph Hisham bin Abdul Malik (r. 691-743), such as the historical Ibn Al-Quṭiya.[8] Keppel Creswell said that the mosque was built later in 864, during the time of the Abbasids (750-1258), when the Aghlabids (800-909) were ruling Ifriqiya.[9] Taha al-Wali presented another opinion that includes all of them, stating that the mosque was founded during the reign of Hassan because whenever Muslims conquered a city, they would initiate it by building a mosque prior to other work. The mosque was later expanded during the reign of Ibn Al-Habhab, and then it was demolished and rebuilt during the Aghlabids’ era.[10]

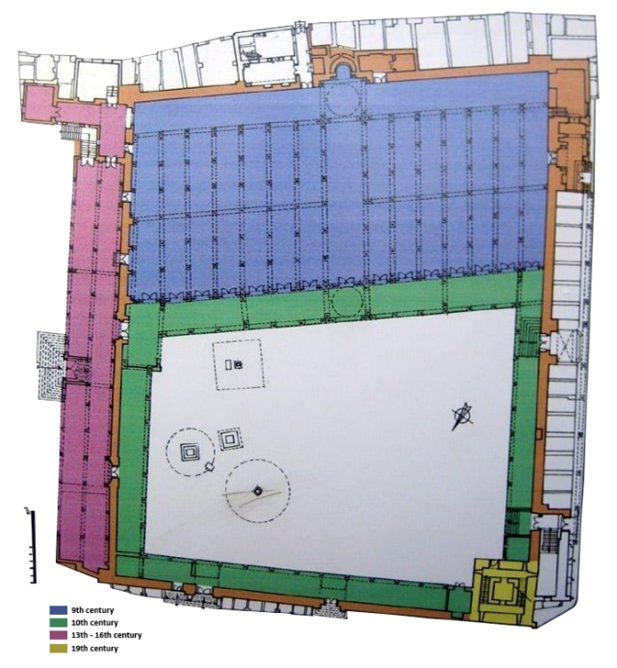

The Aghlabids’ era started at the beginning of the ninth century when the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786-809) sent Ibrahim Ibn al-Aghlab (r. 800-812) as a ruler over Ifriqiya, who established the Aghlabid dynasty and ruled Ifriqiya for a century.[11] Their time was described as a golden age. Ifriqiya witnessed an economic boom, remarkable growth in its artisanship, infrastructure, massive town walls, new forms of monumental architecture, agricultural productivity, availability of raw resources, precious metals, ornate glazed ceramics, metalwork, and textiles.[12] Zaytuna mosque was rebuilt or remodeled based on the order of caliph al-Mustain Billah (r. 862-866) during the reign of Abu Ibrahim Ahmed (r. 856-863), and completed during the reign of Ziyadat Allah (r. 863-864), the sixth and the seventh Aghlabid rulers. This date was carved in an inscription under its mihrab dome, and the mosque’s ninth-century form remains. The mosque has also been subsequently enlarged and restored several times when other dynasties ruled Tunis after the Aghlabids, such as the Fatimids, the Hafsids, and the Ottomans.[13]

Analysis

before the enlargement

Generally, mosques represent Islamic architecture. They are not only considered places for praying, but they are also communal and gathering centers. Most mosques’ forms are derived from the Prophet Muhammad’s mosque in Medina, built in 622. Its type of plan is termed hypostyle or Arab-style mosque, which means a building with a roof supported by several rows of pillars. Tariq Swelim says it is more accurate to describe a series of columns or piers that support arches and, in turn, support the ceiling as riwaq rather than hypostyle; however, the closest word to riwaq in the English language is the word portico.[14] As shown in Figure 2, the Prophet mosque was simply a walled courtyard with three entrances and two sheltered riwaqs, a larger one in the front and a smaller one in the back. The front one functioned as a sanctuary, and its wall was the qibla wall, indicating the orientation for prayer. Other components are derived from Byzantine and Sasanian architecture, such as the mihrab, which is like a niche structure in the qibla wall. There are other components of unknown origin, such as the maqsura, a space that separates the ruler from the other prayers. The minaret also has an unknown origin. It is a tower in the exterior area of the mosque, and it is used to perform adhan, the call for the prayers.[15]

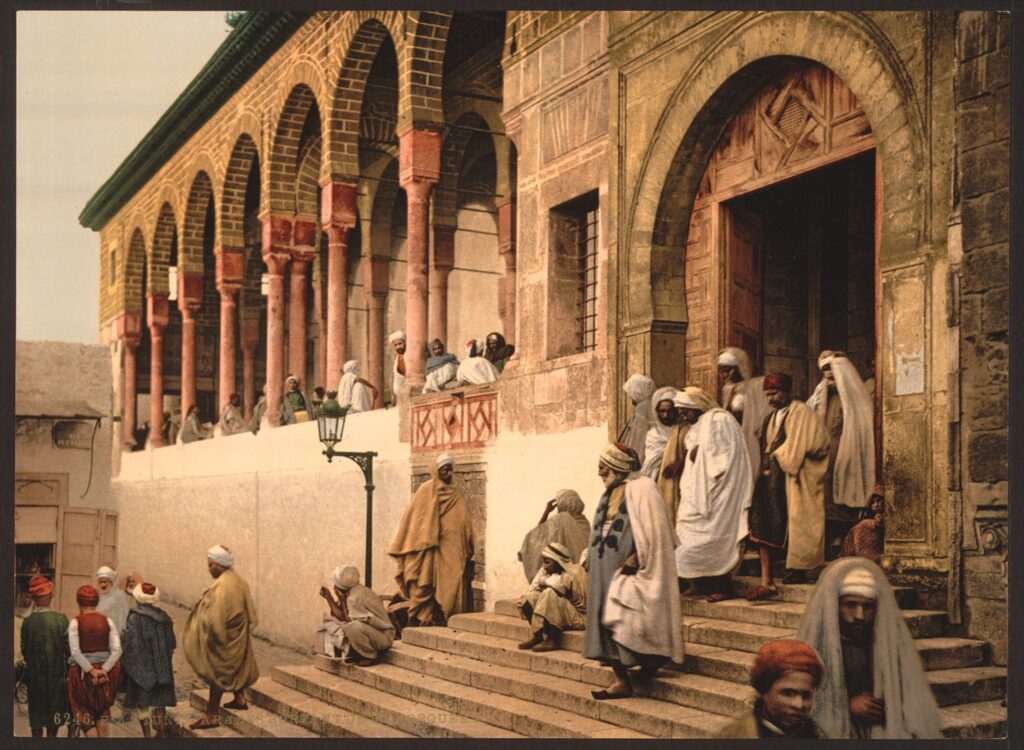

Zaytuna mosque means mosque of the olive tree. According to historians, there are different opinions regarding the reason for its name. Some historians say, “The site is associated with Saint Olivia of Palermo.”[16] Other opinions refer its name to the Quranic verse “an olive neither of the East nor of the West, whose oil would almost glow forth though no fire touched it.”[17] As the mosque glows North Africa with the believing glow.[18] The most accurate opinion is that there was an olive tree on the site where it was built.[19] The mosque is currently located in the old town of Tunis (old Medina) where shops on all sides surround it. As Bloom describes it, “like the Friday mosque of Isfahan in Iran, can hardly said to have an exterior, as most of it blends imperceptibly into the surrounding urban fabric.”[20] It has thirteen doors, two on the south side in front of the wool market, on both sides of the mihrab. The right one opens into the room of the minbar (pulpit), and the left one is Bab al-Khatib, the entry of the Friday sermon’s imam. There are three other doors on the west in front of the cloth market, three on the north in front of the spice market, and five on the east in front el Fekka market.[21] There were only six doors at the time of the Aghlabids, while the other doors were added during the Hafsids era (1229-1574).[22]

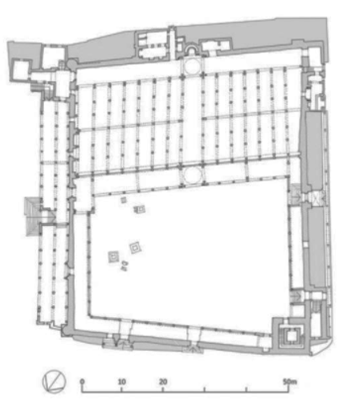

The Zaytuna Mosque today is like a large rectangle. Its main axis points southeast towards the qibla. It is surrounded by a thick stone wall enclosing a sahn, a courtyard paved with reused antique marble. On the southeast side of the courtyard is the prayer hall, sanctuary, which is part of the main structure, that the Aghlabids built, and its entrance is called Bab al-Bahu. There is a dome in its outer face, in the middle of a riwaq located along the façade of the sanctuary, which has a Kufic inscription on the square structure of the dome showing that it was built in 990-991, during the fifth caliph of the Fatimid dynasty, al-Aziz Billah (r. 975-996). On the other sides of the sahn are other riwaqs, built later during the Hafsids era, who also built a ziyada (an additional construction), a funeral patio on the east side of the mosque, maqsuras, and three libraries. There is also a minaret located in the western corner of the mosque, newly built at the end of the nineteenth century.[23]

The Sanctuary (Prayer Hall)

Zaytuna Mosque’s sanctuary model is an Arab-style structure of fourteen arcades creating fifteen aisles, running perpendicular to the qibla wall, but do not reach it as there is a space before the wall, and each arcade consists of six round horseshoe arches.[24] According to Ibn Ashur, the arches’ type were chosen not for a decorative reason but for an architectural reason aiming to increase the ability to resist more pressure.[25] A central transverse arcade attaches the arches, but they do not cut across the center aisle, which is higher and wider than the rest of the aisles. The transverse aisle in front of the qibla wall and the central aisle creates a T-shape. The art historian and archeologist Oleg Grabar explained the T-shape as a formal hallmark of classical Islamic architecture. It emphasizes the mystical religious character of the qibla wall.[26] The roof is formed of a series of wooden beams.[27] In some studies of the mosque, like the one by Bloom, the plan shows skewed aisles (Figure 5), unparalleled and irregular with one another, but this is not noticeable when a person is inside the building. Bloom suggests that this skewing occurred because the materials used in the building were not of equal sizes, such as stone bases, columns, and capitals.[28] Moreover, the mosque has two hundred reused marble columns in various colors, with Corinthian, Byzantine, and Roman capitals supporting the arches, which were probably taken from the ruins of Carthage.[29] The sanctuary columns are topped by cubes covered with ornamented stucco of various designs and transom crowned with cornices.[30]

The Mihrab

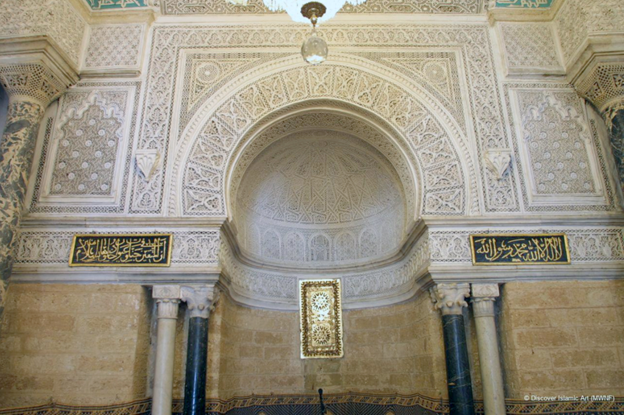

The mihrab’s form is semicircular, which centers on the qibla wall. The type of its frontal arch is also a round horseshoe, supported by four marble columns, white and black columns on both sides in recesses. It is topped with a semi-dome filled with stucco ornaments, which also cover the front part of the arch and the wall above it. The ornaments’ characteristics are similar to those in the arches that carry the dome.[31]

The Domes

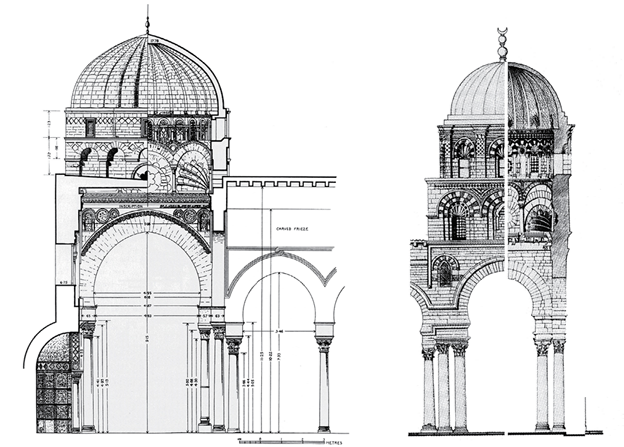

The dome in front of the mihrab is supported by an arched wall, which is part of the qibla wall, in addition to three freestanding arches resting on a pair of engaged columns. Each of them consists of five columns. The arches create a square structure, which consists of an inscription of who built it in simple Kufic. On both faces of the arches, in and out, is another Kufic inscription. It is more advanced and has a different technique than the one above, as shown in Figures 10 and 11. The arches’ soffits and spandrels are also decorated with ornaments that were made of stucco. The ornaments and the advanced Kufic were added during the Hafsid era. The square base is externally decorated with a prominent broadband and contains decorations of small niches and arched shapes on the east, west, and south sides. The north side is not decorated. Above the square structure, there is a transition area, as arches are based on columns. In the corners, there are shapes of shell squinches. Between the shells, there are slightly recessed arches centered with circular windows. The shape of the drum is octagonal. It consists of ten arched windows with painted voussoirs of white and black alternately, while internally, there are small niches between the arched windows, separated by columns with capitals carrying them. Above the drum is a hemispherical ribbed dome consisting of twenty branching ribs. The masonry located between the dome and the drum is also painted white and black alternately.[32][33] The other dome in front of Bab al-Bahu is also similar to the one in front of the mihrab. It is clear that the Fatimids were influenced by the Aghlabids’ architecture, trying to match their dome with another one. Except that columns with Byzantine crowns carry it, and its structure features voussoir of white and red alternately.[34]

from the top of the minaret (MWNF, 2020)

The Hafsids Period

In 1150, the Almohads (1121-1269) took control of Morocco and Andalusia, and they had two capitals, Marrakesh in Morocco and Seville in Andalusia.[35] A few years later, they took control of Ifriqiya and left it in the hands of the Hafsid dynasty. In 1229, the Hafsids gained independence from the Almohads and made Tunis their capital. During their reign, The city flourished, its population increased, and its area expanded. They also enlarged the mosque, replaced the doors, repaired and restored the dilapidated parts, such as the decoration of the mihrab, and made the eastern side that overlooks the Fekka market a funeral patio. On the same side of the mosque, they built a facade that is considered a Hafsid model, especially the window, which has double arches and is built with limestone on a column with a Hafsid crown. The Hafsid Sultan Abu Amr Othman (r. 1435-1488) built maydaa’, a place for Ablution in the spice market, close to the mosque. It has various arches, polylobed, horseshoe, and recti-curviligne, made of black and white marble paving alternately. It is also distinguished by luxurious decoration, in which white alabaster is inlaid with black marble on complex geometric shapes.[36] They took great interest in spreading the Almohads ideology, which was reflected in the Zaytuna mosque.[37] As they established three halls for preserving books, the Abu Faris (or Ahmadiya) library in 1419, which was named after the Sultan Abu Firas Abdulaziz II (r. 1394–1434), the Abu Amr Othman library in 1450, and the Abdaliya (or Sadiqiya) Library in 1500.[38]

The Minaret

The minaret located in the western corner of the courtyard was built in 1894. However, other opinions claim that there was a minaret, but it was almost going to collapse, so the late nineteenth-century one replaced it.[39] Commonly, In the Maghreb and Tunisia, the Minaret is called Sawma’a, which is mentioned in several stories about the Zaytuna mosque since it was built at the time of Hassan. Additionally, the term Sawma’a is also used to refer to a place of worship, and some historians say that the mosque was built in a place of a Sawma’a that was for monks. It is also said that it was built over a Byzantine church. Some Christian graves were recently discovered on the mosque’s eastern side dating back to the fourth century. In addition, some Roman monuments were found under the current minaret.[40] All these monuments indicate the validity of these accounts. Hence, it is best to consider what Ibn Abi Dinar said that when the site was taken as a mosque, it turned the Sawma’a into the place of the adhan. At the time, its height was about four meters. Then the Hafsids rebuilt it in a square shape and increased its height to thirty meters. Then the Muradids (1631-1702) built at its top five riwaqs, and it lasted in its state until it was almost going to collapse, so during Husainids’ reign of Tunis (1705-1957), it was demolished and rebuilt in 1894 to the state it is in now.[41]

A Comparison between the Kairouan Mosque and Zaytuna Mosque

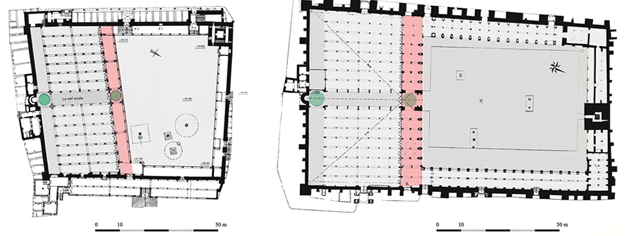

Kairouan mosque’s model is used in other mosques in the region, such as the Zaytuna mosque in Tunis and the Fatimid mosque at Mahdiyya, built in 916.[42] When both plans of Kairouan Mosque and Zaytuna Mosque are presented beside each other as in Figure 15, a significant similarity appears between them, as both were rebuilt in the Aghlabid era in the same period, same people, and same materials. Even though the scale of the Zaytuna mosque is almost half the scale of the Kairouan mosque, both were constructed with the same technique. Both are shaped of enclosures around courtyards surrounded by riwaqs; Arab-style sanctuaries with horseshoe arches running perpendicular to the qibla wall, transverse and central aisles creating a T-shape, series of wooden beams forming their roofs, a dome in front their mihrabs, and another dome in front their sanctuaries’ entrances. However, their minarets are different, and Zaytuna’s domes are smaller. Additionally, Kairouan Mosque has more lateral and transverse aisles, and its arches spans are wider.[43]

Conclusion

The Zaytuna Mosque recorded its mark, leaving a reference that can be referred to, allowing to understand the development of Islamic architecture and that Muslims in their early days did not have a great interest in building monuments. When the Muslims entered North Africa during the Umayyad era, they founded the city of Kairouan and built a mosque in it. At that time, the Byzantines were stationed in the city of Carthage. After a few years, the Muslims were able to defeat the Byzantines, destroy their city, and founded the city of Tunis, where they built the Zaytuna Mosque. Both mosques were only places for prayer that were not valued architecturally. The interest in constructing these mosques as seen today did not begin until the Abbasids era. Both mosques were rebuilt similarly when the Aghlabids started ruling Ifriqiya, believing that these mosques should be Islamic landmarks.

Today, the mosque is located in the old town of Tunis, surrounded by shops on all sides. This location raised the value of the mosque. Indeed, when there is a movement of people around the mosque, it will give the mosque a higher social value, making both the sellers and the customers more interested in the mosque. It makes the sellers think about using the mosque and prayer times to sell their goods, and it makes the customers make the mosque a place for their meetings and appointments. In fact, this is one of the main roles which mosques play among Muslims as a place for gathering and stimulating social matters.

The structure of the Zaytuna mosque, which was built during the Aghlabid era and continues to this day, was identical to other great mosques that were built at its time or shortly before it. The mosque has a remarkable resemblance to the Mosque of Kairouan and many other components from the Mosque of Cordoba and the Mosque of Damascus. Later, these components continued in later mosques, characterizing them wherever they were built. Nevertheless, some components can only be seen in North Africa in particular. What distinguishes Zaytuna Mosque is that it consists of a courtyard surrounded by riwaqs. Its sanctuary consists of columns connected by horseshoe arches that run perpendicular to the qibla wall, a central aisle, and a transversal aisle. They form a T-shape, ostentatious domes, richly ornamented mihrab, and a newly built square minaret. The feature which certainly breaks the rules and shows confidence and independence is the sanctuary entrance’s riwaq, which is crowned by a dome. Accordingly, Tunis was distinguished by its mosque, which preserved its authenticity with cultural accumulation.

[1] Oleg Grabar, The Formation of Islamic Art (London: Yale University Press, 1978), 125.

[2] Felix Arnold, Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History (New York: OUP, 2017), 2.

[3] Idris El Hareir and Ravane Mbaye, The Spread of Islam Throughout the World (Paris: UNESCO, 2011), 381.

[4] Meera Lester, Sacred Journeys: Your Guide to the World’s Most Transformative Spaces, Places, and Sites (Massachusetts: Simon and Schuster 2019), 102.

[5] Jonathan M. Bloom, Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800 (London: Yale University Press, 2020), 38.

[6] Idris El Hareir and Ravane Mbaye, The Spread of Islam Throughout the World (Paris: UNESCO, 2011), 383.

[7] M. Elfasi and I. Hrbek, Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century (Paris: Unesco, 1988), 239.

[8] David James, Early Islamic Spain: The History of Ibn Al-Qūṭīya : a Study of the Unique Arabic Manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, with a Translation, Notes, and Comments (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009), 60.

[9] Keppel Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940), 323.

[10] Taha al-Wali, Mosques in Islam/ المساجد في الاسلام (Beirut: Dar El Ilm Lilmalayin, 1988), 564-565.

[11] Wijdan Ali, The arab contribution to islamic art: from the seventh to the fifteenth centuries (Cairo: American Univ in Cairo Press, 1999), 127.

[12] Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Fenwick and Rosser-Owen Mariam, The Aghlabids and their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa, (Massachusetts: BRILL, 2011), 3.

[13] Keppel Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940), 323.

[14] Tarek Swelim, Ibn Tulun: His Lost City and Great Mosque, (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2015), 283.

[15] Josef W. Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index, (Oxon: Taylor & Francis, 2006), 518-520.

[16] World Digital Library, Arabs Leaving Mosque, Tunis, Tunisia, Library of Congress [website], https://www.wdl.org/en/item/8872/ (accessed 8 November 2020).

[17] The Qur’an 24:35

[18] Taha al-Wali, Mosques in Islam/ المساجد في الاسلام (Beirut: Dar El Ilm Lilmalayin, 1988), 562.

[19] Keppel Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940), 321.

[20] Jonathan M. Bloom, Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800 (London: Yale University Press, 2020), 40.

[21] Keppel Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940), 323.

[22] Muhammad Al Aziz ibn Ashur, Zaytuna Mosque: The Landmark and its men/ جامع الزيتونة: المعلم ورجاله. (Tunis: Dar Siras lil-Nashr, 1991), 30.

[23] Keppel Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940), 321-324; Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Fenwick and Rosser-Owen Mariam, The Aghlabids and their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa, (Massachusetts: BRILL, 2011), 270.

[24] Jonathan M. Bloom, Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800 (London: Yale University Press, 2020), 40.

[25] Muhammad Al Aziz ibn Ashur, Zaytuna Mosque: The Landmark and its men/ جامع الزيتونة: المعلم ورجاله. (Tunis: Dar Siras lil-Nashr, 1991), 19.

[26] Oleg Grabar, The Formation of Islamic Art (London: Yale University Press, 1978), 124-125.

[27] Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Fenwick and Rosser-Owen Mariam, The Aghlabids and their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa (Massachusetts: BRILL, 2011), 270.

[28] Jonathan M. Bloom, Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800 (London: Yale University Press, 2020), 39

[29] Juan Eduardo Campo, Encyclopedia of Islam )New York: Infobase Publishing, 2009), 721.

[30] Keppel Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940), 323.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ashur, Zaytuna Mosque: The Landmark and its men/ جامع الزيتونة: المعلم ورجاله. (Tunis: Dar Siras lil-Nashr, 1991), 14-16.

[33] Keppel Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940), 323; Muhammad Al Aziz ibn

[34] Corisande Fenwick and Rosser-Owen Mariam, The Aghlabids and their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa, (Massachusetts: BRILL, 2011), 271.

[35] Jonathan Holt Shannon, Performing al-Andalus: Music and Nostalgia across the Mediterranean, (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2015), 88.

[36] Ashur, Zaytuna Mosque: The Landmark and its men/ جامع الزيتونة: المعلم ورجاله. (Tunis: Dar Siras lil-Nashr, 1991), 32.

[37] Ian Richard Netton, Encyclopaedia of Islam, (New York: Routledge, 2013), 207

[38] David H. Stam, International Dictionary of Library Histories, (New York: Routledge, 2001), 112

[39] Bernard O’Kane (2019). Mosques: The 100 Most Iconic Islamic Houses Of Worship. New York: Assouline Publishing.

[40] Taha al-Wali, Mosques in Islam/ المساجد في الاسلام (Beirut: Dar El Ilm Lilmalayin, 1988), 560.

[41] Ibid, 566-568.

[42] Jonathan M. Bloom, “On the Transmission of Designs in Early Islamic Architecture” Muqarnas 10, (1993): 22.

[43] Glaire D. Anderson, Corisande Fenwick and Rosser-Owen Mariam, The Aghlabids and their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa, (Massachusetts: BRILL, 2011), 273-274.